This section provides guidance for investors on identifying and assessing actual or potential impacts on Indigenous peoples at both the portfolio and individual investment level, drawing on the Investor Toolkit on Human Rights. This includes the assessment of investee companies’ human rights due diligence processes, and the assessment of investee companies’ human rights outcomes, throughout the investment cycle.

The assessment of the quality of potential investee companies’ human rights due diligence processes with respect to Indigenous peoples will vary depending on the specific context of a company. For example, appropriate policies and processes for mining companies are likely different from those of downstream food and beverage manufacturing companies.

The assessment of investee companies’ human rights outcomes should go beyond policy commitments and due diligence processes and address the actual outcomes and impacts of companies on Indigenous peoples, as well as how these are remedied. It should go beyond assessing company inputs and prioritize the perspectives of those Indigenous communities and individuals whose human rights may be affected. Where this is not possible, investors should, in accordance with the UN Guiding Principles, consult with credible, independent expert resources, including human rights defenders and others from civil society.223

Case Study: Glencore Corporate Human Rights Benchmark

In the 2022 iteration of the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB), the mining company Glencore ranked #17 out of 129 companies, meaning that the company fulfils many of the criteria for achieving a high score according to the CHRB methodology. Yet while Glencore has achieved a high score on the benchmark, civil society organizations have reported on Glencore’s alleged systematic involvement in human rights abuses.224

As such, whereas benchmark methodologies provide a useful tool for businesses and investors to understand gaps in their due diligence processes, and help them understand how to fil those gaps, the scores themselves cannot substitute the need to consider the perspectives of those affected by company activities.

Why special attention to Indigenous rights in due diligence is required

While companies that have strong due diligence process in general are more likely to avoid infringing on the human rights of all people, as the Working Group on Business and Human Rights recognizes, given the specificities of adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples, generic assessments may not be sufficient to fully identify and address potential human rights risks, particularly with regard to collective rights to land, resources and self-determination.225 Thus, the assessment of investee companies’ due diligence processes and human rights outcomes should also specifically focus on collective rights of Indigenous peoples.

Businesses can be involved in adverse human rights impacts both by actions and omissions. Omission may entail, for example insufficient attention to Indigenous rights in due diligence processes. However, effective investor due diligence requires not just assessments of due diligence processes and gaps but also heightened attention to signs that due diligence is not conducted in good faith, e.g., a company or third parties connected to a company (such as contractors or government agencies) that use coercive tactics.

Why investors should require transparent disclosure of FPIC processes

Policies and certification schemes are by themselves not a guarantee that Indigenous rights are or will be respected throughout a business’ operations or value chain. This means that adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples largely go unnoticed by investors until Indigenous peoples and civil society organizations denounce those impacts. Often, it may go unreported due to fear of reprisals, such as assassinations, criminalization, lawsuits, threats, defamation, etc.

The existence of policies that mention Indigenous people is often considered by investors and benchmarks as a positive indicator. However, the existence of policies is not a reliable indicator if the same company fails to transparently disclose its operations and value chain in a manner that enables verification that Indigenous peoples’ rights are respected. For example, a company that has a policy on Indigenous peoples may respect and have partnerships with Indigenous peoples in one country but be involved human rights abuses in another country, including through subsidiaries or joint ventures.

Therefore, the metric should not be ‘does a company have a policy on Indigenous rights or FPIC?’ but rather, ‘does publicly available evidence exist that allows for independent verification that the company respects Indigenous peoples’ rights and has consent at each operational site or concession?’

An example of how information is being disclosed in some sectors includes the High Carbon Stock Approach (HCSA) Quality Assurance process, which includes a peer review process of a company’s HCSA report, including with respect to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous peoples, which is then made available on the HCSA website.

Where companies fail to disclose information necessary to understand their actual or potential human rights impacts, and whether and how they have obtained FPIC through Indigenous peoples’ legitimate decision-making processes and in accordance with international human rights law, that may itself be a “red flag” that investors need to enhance their due diligence.

Case Study: Report on Canadian companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange

A study conducted by the Justice and Corporate Accountability Project reviewed violent incidents involving 28 Canadian companies from 2000 to 2015 across various regions, often affecting Indigenous peoples. The study found that the companies were connected to 44 deaths, 403 injuries, and 709 cases of criminalization, but only reported on 24% of deaths and 12% of injuries in their mandatory reports.226

Case Study: Tahoe Resources

Canadian mining company Tahoe Resources failed to disclose the extent of community and Indigenous opposition to its Escobal mine in Guatemala. After a series of lawsuits and violent conflicts, the mine was suspended by a Guatemalan court. Tahoe’s shares plummeted from a high of $27 and was eventually sold to Pan American Silver for about $5 a share.227

Why investors should require transparent disclosure of companies’ value chains

Independently verifiable information is critical for enabling investors and affected communities to assess the quality of companies’ due diligence processes, including with regards to companies’ value chains. Examples of relevant disclosure include:

- Some companies have started mapping their forest footprints, which includes disclosure on the footprint of their value chain including impacts on the rights of Indigenous peoples and affected communities. Examples of pilot studies some companies have undertaken (albeit to a limited scope) include those of Unilever, Colgate, and Nestle.

- Triodos Bank publicly discloses information on each organization to which it lends money.

- Wilmar publicly discloses the grievances filed in its operations and value chain.

- Companies in the palm oil value chain, such as Nestle, have started disclosing a list of their suppliers via the Universal Mill List.

While such disclosure is not common in most sectors and commodity value chains, these examples show that it is possible, and could extend to other sectors and commodities. An interim step for investors entails setting clear expectations and engaging with investee companies about transparent disclosure of their operations, value chains, impact assessments, and FPIC processes and outcomes.

7.1 Map actual or potential adverse impacts at investment universe and portfolio level

This section provides guidance for investors to understand the risk of actual or potential impacts on Indigenous peoples at portfolio or investment universe level. This includes companies that may cause or contribute to adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples through their own activities, or companies that may be linked to adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples by their business relationships.

Identify and map industry and product risk exposure

Sectors and products in which companies may cause, contribute to, or be directly linked to adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples include, but are not limited to:

- Extractives: Mining, oil and gas, coal

- Renewables: Hydropower, wind, solar

- Agribusiness: Palm oil, sugar, cattle, biofuels, fisheries, forestry, rubber, etc.

- Conservation: Carbon and biodiversity credits, conservation programs, etc.

- Infrastructure: Highways, airports, ports, pipelines, renewable energy projects, etc.

Moreover, midstream, and downstream companies can be directly linked to adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples by their business relationships in their upstream value chain. Examples include:

- Food and beverage: sourcing of agricultural products such as palm oil

- Car and battery manufacturers: sourcing of minerals

- Pulp and paper: sourcing of forestry products

- Car seat and car manufacturers: sourcing of leather

- Livestock and animal feed companies: sourcing of soy

- Tire manufacturers: sourcing of rubber

- Metals refineries: sourcing of minerals

- Companies that purchase carbon or biodiversity credits

In addition, large development projects, such as infrastructure or mining projects, involve not only an operating company but also providers of products and services such as suppliers of machinery and equipment, which also have a responsibility to conduct their own downstream due diligence.

Case study: Car manufacturers linked to illegally deforested lands

In December 2022, the Environmental Investigation Agency published a report showing that major car manufacturers importing leather for car seats were at elevated risk of sourcing leather from illegally deforested lands and cattle raised illegally on Indigenous lands. According to the report, car manufacturers, including but not limited General Motors, Daimler, Stellantis, Volkswagen, and Ford, are alleged to have sourced car leather from automotive leather manufacturers such as the Lear Corporation, which in turn allegedly sourced leather from JBS, Vancouros, and Viposa, all of which according to the report, regularly bought cattle directly from illegal farms.228

Case Study: Blood gold from the Brazilian Amazon

In the last few years, illegal gold mining has had devastating consequences for Indigenous peoples across the Amazon, and there is compelling evidence that the gold ends up in global value chains.

In the case of Brazil, tech companies, such as Apple, Microsoft, Intel, Tesla, Ford, General Motors, Samsung, Sony, and Volkswagen, are alleged to have bought gold from refineries investigated by Brazilian authorities for buying illegal gold mined in the Amazon.229

Separately, investigations on gold imported by Swiss refineries found that a fifth of imports came from Brazilian Amazon provinces, most of which, were probably mined illegally. In June 2022, Swiss refineries pledged to take measures not to import illegally mined gold from Indigenous territories,230 but Canada, the largest importer of gold from the Brazilian Amazon, made no such pledge.231

Identify and map geographical risk exposure

To understand their geographical risk exposure, investors should identify regions in which their investee companies may be involved in adverse impacts through activities that they cause, contribute to, or to which they may be linked by their business relationships. Relevant questions for investors to consider include:

- Do investee companies have own activities or operations in regions where Indigenous peoples may be affected?

- Do investee companies have subsidiaries, or participate in joint ventures that have activities or operations in regions where Indigenous peoples may be affected?

- Do entities in investee companies’ value chain have activities in regions where Indigenous peoples may be affected (e.g., in relation to suppliers, downstream value chain, financial transactions)?

Investors should be cautious that in many regions, Indigenous peoples are affected by domestic as well as foreign companies. Many companies affecting Indigenous peoples globally are listed on major stock exchanges, such as the Toronto Stock Exchange232 and the London Stock Exchange.233

According to a report by Indigenous Peoples Rights International (IPRI) and the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, Latin America (75%) and Asia-Pacific (18%) are the regions with the most attacks against Indigenous human rights defenders (IHRDs).234 The report finds that:

- The highest numbers of attacks against IHRDs occurred in Honduras, Peru, Mexico, Guatemala, Brazil, the Philippines, and Colombia.

- In the cases companies were publicly linked with attacks against IHRDs, the majority were headquartered in Honduras (72), Guatemala (54), Canada (39), USA (37), Mexico (32), and China (28).

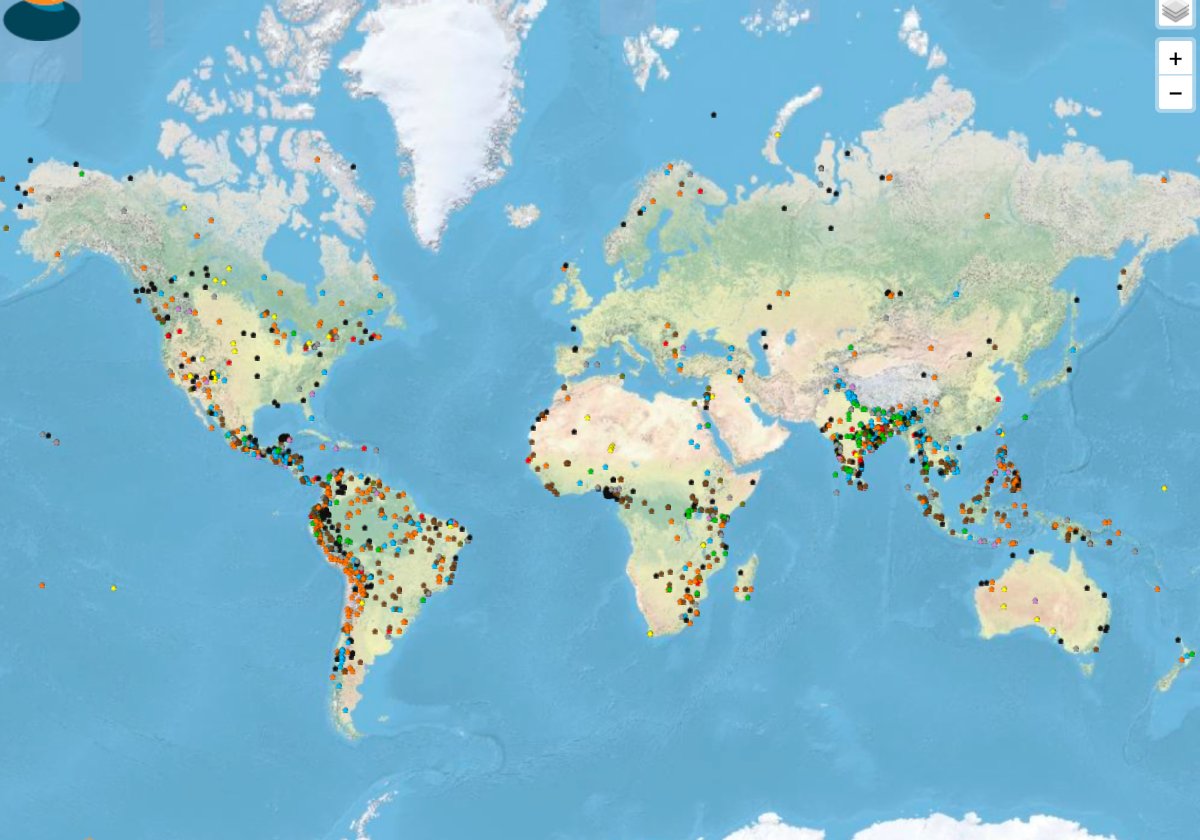

Figure 3. Overview of Environmental Justice Atlas documented socio-environmental conflicts where Indigenous peoples or traditional communities were affected.

Examples of tools to conduct high-level mapping of geographical exposure include:

- EJAtlas allows users to filter for cases of socio-environmental conflicts according to numerous factors such as, cases where Indigenous peoples were affected, and by sector.

- Verisk Maplecroft has developed country-based Indigenous rights industry risk indicators.

7.2 Identify actual or potential impacts

This section includes questions and data sources that investors may use as guidance to assess companies’ due diligence processes and to identify actual or potential impacts. This also includes “red flags” that investors may use as signals to further escalate due diligence. While these questions and red flags aim to facilitate due diligence, investors may need to adopt their due diligence as appropriate to the size of the investee company, risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context of its operations. Data sources to help identify actual or potential impacts are provided in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Table 2. Resources to help identify actual or potential impacts on Indigenous peoples

| Resource | Description | Type | Sector | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Tracks NGO campaigns and reports related to companies and investors, including with a specific focus on Indigenous peoples. | Database | All | Global | |

News and reports (in Spanish) of socioenvironmental conflicts, including conflicts related to mining, energy, forestry, and agribusiness. | Database; map | Mining; forestry; agribusiness; energy | Latin America | |

Database of harmful projects financed by banks. | Map; reports | Various | Global | |

Socio-environmental conflicts related to projects and extractive activities. | Map; reports | Various | Global | |

Map of mining-related socio-environmental conflicts in Latin America. | Map | Mining | Latin America | |

Map of mining-related socio-environmental conflicts in Chile (in Spanish). | Map; reports | Various | Chile | |

Database of land conflicts in India. | Map; reports | Various | India | |

Reports on mining companies and concessions in Ecuador, including overlap with Indigenous territories | Map; reports | Mining | Ecuador | |

Cases of complaints with the OECD National Contact Points (NCP) system. | Map; reports | Various | Global | |

News and allegations relating to the human rights impacts of over 20,000 companies | Reports | Various | Global | |

Weekly updates on business and human rights. | Reports | Various | Global | |

Data on the human rights practices of 103 companies active in producing minerals for the renewable energy and electric vehicle sectors. | Dataset | Mining | Global | |

The report includes a dataset (Excel-file) of allegations of human rights abuses in the renewable energy sectors between 2010 and 2019. | Dataset | Renewables | Global | |

Evaluations of major brands on their deforestation and human rights policies and impacts. The Keep Forests Standing Scorecards evaluate the policies and practices of major brands and banks involved in deforestation and human rights impacts. | Reports | Various; food and beverage; banks | Global | |

Assessments of commodity producers, processors, and traders, including with respect to Indigenous rights. It also has a media monitor covering topics related to associated topics, including human rights. | Benchmark; reports | Agribusiness | Global | |

Reports on companies involved in Indigenous rights violations in the Amazon. | Reports | Various | Amazon region | |

Data on deforestation, conversion of natural ecosystems and associated human rights abuses of companies. | Data provider | Financial services; agribusiness; food and beverage; other | Global | |

Public list of grievances of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). | Grievances | Palm oil | Global | |

Monthly reports on deforestation in global commodity chains, including information on overlapping or nearby Indigenous lands. | Reports | Agribusiness | Brazil | |

Research on Canadian mining companies operating in Canada and abroad, with a focus on Indigenous rights. | Reports | Mining | Global | |

Dataset of ESG risks covering over 200,000 companies, including assessments on incidents related to Indigenous peoples (according to its methodology documents). | Data provider | Various | Global | |

ISS (Institutional Shareholder Services) Norm-Based Research | Norm-based screening which monitors companies, including with respect to international standards on Indigenous peoples’ rights (according to its methodology documents). | Data provider | Various | Global |

Google, Twitter, and social media search | Indigenous rights violations are often reported first through Indigenous peoples’ own media channels, and then by NGOs. Search strings such as “[Company name] [Indigenous rights]” or “[Company name] [Indigenous rights violations],” as well as searches in local languages can provide detailed and timely information. |

Table 3. Benchmarks to assess companies’ due diligence policies

| Resource | Description | Type | Sector | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Dataset containing indicators on deforestation and human rights commitments of the 500 companies with the greatest exposure to tropical deforestation. | Dataset; benchmark | Financial services; agribusiness; food and beverage; other | Global | |

The Lead the Charge Scorecard assesses automakers’ efforts to eliminate fossil fuels, environmental harms, and human rights abuses from their supply chains, including with respect to Indigenous rights. | Benchmark | Automobiles | Global | |

Benchmark of the human rights policies and practices of the largest publicly traded wind and solar companies in the world, including with respect to Indigenous rights. | Benchmark | Renewables | Global | |

Evaluates the policies of banks financing 300 companies in forest-risk commodity supply chains, including whether the banks have FPIC requirements. | Dataset; benchmark | Financial services; agribusiness; forestry; mining | Global | |

Assessments of commodity producers, processors, and traders, including with respect to Indigenous rights. It also has a media monitor covering topics related to assessment topics. | Benchmark; reports | Agribusiness | Global | |

Assessment of palm oil buyers’ policies with respect to deforestation and human rights. | Benchmark | Palm oil | Global | |

Benchmark of companies’ human rights policies and due diligence processes. | Benchmark | Various | Global | |

Various indicators on mining companies, including with respect to Indigenous peoples and FPIC. | Benchmark | Mining | Global | |

Assessment of the extent to which banks have implemented the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. | Benchmark | Banks | Global |

Table 4. Additional resources to identify and assess impacts

| Resource | Description | Type | Sector | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Maps of Indigenous lands and territories, and their legal status. | Map | Global | ||

Tracks deforestation in the Andean Amazon, including related to Indigenous territories. | Map; reports | Mining; agrobusiness; oil and gas | Andean Amazon | |

Maps of forest change and commodity concessions, including on Indigenous lands. | Map; concessions | Agribusiness; mining; oil and gas | Global | |

Maps of Indigenous lands and territories, and their legal status. | Map | Global | ||

Map showing real-time applications filed with the Brazilian Mining Agency including overlap with Indigenous lands. | Map; concession | Mining | Amazon region | |

Real-time monitoring of mining impacts in the Amazon, using satellite images and machine learning. | Map | Mining | Amazon region | |

Maps of deforestation and commodity concessions in South-East Asia, including deforestation on Indigenous lands. | Map; concessions | Palm oil; forestry; mining; other | South-East Asia | |

Global map of agricultural land acquisition, lease, concession, and exploitation permits. | Map; projects | Agribusiness; forestry; mining; oil and gas | Global | |

Map of Indigenous peoples and Community Conserved Territories and Areas (ICCA). | Map | Global | ||

Information on the supply chains of companies involved in commodity-driven deforestation. | Various | Agribusiness | Various | |

Information on the exposure to deforestation risk of financial institutions and funds. | Various | Financial services; agribusiness | Various | |

Research on deforestation and human rights risks of companies involved in global commodity value chains. | Reports | Agribusiness | Global | |

Reports on deforestation and climate change related to companies involved in global commodity value chains. | Reports | Various | Global | |

Reports on corporate environmental and human rights abuses, including attacks against Indigenous human rights defenders. | Reports | Various | Global | |

Reports on deforestation and climate, including land-grabbing and Indigenous rights. | Reports | Various | Global | |

Reports on human rights abuses in forest-risk value chains. | Reports | Various | Global | |

Maps of Indigenous territories, deforestation, and business activities in the Amazon. | Reports; maps | Various | Amazon Region | |

A tool for companies to identify the risks in relation to countries and products/services. The tool uses reports sourced from a variety of different organizations such as the International Work Group on Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), Amazon Watch as a basis for their results. | Reports | Various | Global | |

Community alerts on illegal activities and human rights issues. | Map; reports | Various | Cameroon; Democratic Republic of Congo; Ghana; Liberia; Côte d’Ivoire; Peru | |

Maps including land use and presence of Indigenous peoples in the Congo basin. | Map; concessions | Various | Cameroon; Democratic Republic of Congo | |

Reports on attacks against human rights defenders. | Reports | Mining | Global |

Note. The various maps provided in this table are provided for indicative purposes and may not necessarily be complete or fully accurate.

Understand the geographical business and human rights context

Where investors have identified exposure to companies associated with high-risk industries and exposure to Indigenous lands and territories, relevant questions to consider include:

- Do Indigenous communities have legal tenure of their lands, territories, and resources in line with international human rights law? Lack of legal tenure indicates heightened risk of violations of their rights.

- Does the country have a legal framework for obtaining Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous peoples in accordance with international human rights law?

- Are there signs of adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples or conflicts previously caused by companies or governments in the region?

- Are there other third parties that may affect the rights of Indigenous peoples, such as illegal loggers, wildcat miners, unauthorized settlers, or illicit groups?

- Are there any ongoing land disputes that may be exacerbated by the presence of companies or other third parties?

- Have national laws, such as regulation related to mining, oil and gas, energy, and agribusiness projects, been criticized by Indigenous organizations or NGO reports for failing to consult with Indigenous peoples about the regulation, or for undermining Indigenous rights?

- Has the government allocated concessions on Indigenous territories to private sector actors without consulting and obtaining consent of Indigenous peoples? Is there a history of land allocations that fail to respect Indigenous peoples’ rights in the country?

Guidance on identifying Indigenous peoples has been provided by the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative (ASI) Indigenous Peoples Advisory Forum: Criteria for the Identification of Indigenous Peoples.

Table 6. Resources for understanding the human rights context

| Resource | Description |

|---|---|

Allows users to explore observations and recommendations made by the international human rights protection system. Investors may use it, e.g., to filter as follows:

| |

Yearly publication of the International Work Group on Indigenous Affairs covering the experiences of Indigenous peoples in over 60 countries over the world. | |

Reports on violations of Indigenous peoples’ rights, with a focus on Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Philippines, and India. | |

Country by country information on minorities and Indigenous peoples. | |

Maps of Indigenous lands and territories, and their legal status. | |

Summaries of country reports on the state of Indigenous peoples’ rights. | |

Interactive map of socio-environmental conflicts related to projects and extractive activities. Out of a total of approximately 3700 cases, 1500 involve Indigenous peoples. | |

Native Land tracks Indigenous territories, treaties, and languages across the world. | |

Provides qualitative and quantitative data on the forest tenure rights of Indigenous peoples, Afro-descendant peoples, local communities, and the women within those communities. | |

A tool for companies to identify the risks in relation to countries and products/services. The tool uses reports sourced from a variety of different organizations such as IWGIA and Amazon Watch as a basis for their results. | |

Dataset and maps of violent conflicts, with local conflict-level information. | |

Industry-specific and geospatial Indigenous rights risk indices. | |

Thematic and country reports on the situation and rights of Indigenous peoples. | |

Country reports on human rights defenders. |

Questions and red flags to consider in due diligence

Impacts that a company may cause or contribute to through its own activities

Where investors have identified that a business might cause or contribute to adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples’ rights through its own activities, questions to consider in investment due diligence and engagement include:

General

- Does the company have any operations on or near Indigenous lands or territories, or activities that may otherwise affect Indigenous peoples’ resources, including lands, air, waters, coastal seas, sea-ice, flora, and fauna?

- Has the company identified and disclosed information on potentially affected Indigenous communities?

- What is the track record of the company’s executives, board, and major shareholders with respect to Indigenous peoples’ rights?

Policy

- Does the company have a policy commitment to respect the rights of Indigenous peoples, including the right to Free, Prior, and Informed consent, which includes the right to withhold consent? What’s the company’s policy on situations where a community does not give consent?

- Does its policy set out procedures and responsibilities for implementing human rights due diligence?

- Does the company have a policy on non-retaliation against human rights defenders?

Due diligence

- Does the company have an internal system and clear responsibilities for carrying out due diligence to identify, assess, and mitigate/prevent adverse human rights impacts on Indigenous peoples? Does relevant staff have relevant expertise on Indigenous peoples’ rights and relevant geographic context?

- Does the company have a grievance mechanism to receive, investigate, and address complaints of Indigenous peoples? Have potentially impacted communities been consulted about the design and implementation of the grievance mechanism?

- Has the company carried out community-level Human Rights Impact Assessments (HRIA) in partnership and consultation with potentially impacted communities to identify and assess actual or potential impacts on their rights and livelihoods?

- What actions has the company taken to avoid contributing to adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples caused by third parties, such as government agencies, joint venture partners, contractors, and security forces?

- Does the company (or third parties connected to the company) respect Indigenous peoples’ own decision-making processes without interfering; without seeking to negotiate agreements in violation of Indigenous peoples’ own laws, traditions, or customs?

Consent

- Where the company has entered an agreement with a State or government agency, e.g., about land use permits, have potentially impacted Indigenous peoples been consulted about, and given their consent to, the agreement?

- Has the company obtained Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous peoples, including a written agreement specifying the terms and conditions of the agreement? Which communities and legitimate representative institutions have given consent?

- Where a company has multiple operational sites, concessions, licenses, or permits that affect Indigenous lands territories and resources, including for exploratory activities, has consent been granted for each of those? Are there any sites, licenses or permits to which consent has not been given?

Response to identified adverse impacts

- Has the company consulted with potentially impacted Indigenous peoples or civil society organizations with regards to appropriate actions to cease, prevent, mitigate impacts, and provide or cooperate in remediation?

- Has the company established a time-bound plan to cease the adverse impact and provide or enable remedy?

- What steps has the company taken to ensure the non-repetition of adverse impacts? Has the company adopted any changes to its policies, processes, management, or board oversight?

Red flags in policy commitment

Corporate policies often mention Indigenous communities or FPIC; however, they often have loopholes. Moreover, larger companies tend to have more policies in place compared to smaller companies; however, this does not necessarily mean that they are better at respecting rights across their operations and value chain. The following are red flags in policy commitment that investors may look out for to instigate further due diligence:

Lack of due diligence

- Lack of due diligence policy that sets clear responsibilities for oversight and implementation of due diligence processes.

- Lack of policy or process to enable remedy through a grievance mechanism, including steps for receiving, investigating, and providing or enabling remedy.

- Lack of policy that requires business partners to respect human and Indigenous rights.

Omission of Indigenous rights

- Mentioning Indigenous people or communities in policies, but not explicitly recognizing and committing to respect the rights of Indigenous peoples in accordance with internationally recognized standards and instruments on the rights of Indigenous peoples, including the UNDRIP.

- Lack of commitment to respect Indigenous rights and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, including the right to withhold consent.

- Weak commitment, such as commitment to “free, prior, and informed consultation.”

- Policy that stresses that FPIC “does not require unanimity.” Such language can be divisive, and it suggests that the company may not respect Indigenous peoples’ own decision-making systems.

- Policy that stresses that Indigenous peoples do not have a “veto right.” As the Expert Mechanism on the Right of Indigenous Peoples has noted, such arguments “largely detract from and undermine the legitimacy of the free, prior and informed consent concept.”235

- Policy that requires the company to only adhere to national legislation, or to industry standards that do not require respect for internationally recognized rights of Indigenous peoples.

- Referring to Indigenous peoples solely as vulnerable groups or stakeholders rather than legitimate rights-holders.

Red flags in impact assessments

Impact assessments should be carried out in a participatory manner with potentially affected Indigenous communities, in a manner that is consistent with international standards on Indigenous rights. Some red flags include:

- Lack of an environmental and social impact assessment (ESIA) or human rights impact assessment (HRIA) or lack of disclosure of impact assessments.

- Relying only on domestic law or industry standards that are not consistent with international human rights standards on Indigenous peoples’ rights.

- Lack of evidence of Indigenous peoples’ involvement in designing the agenda, nature, and timelines of the impact assessments.

- Not including Indigenous rights and perspectives, such as relationship to lands and sacred sites, or cultural and spiritual impacts.

- Lack of assessment on the impacts on the rights and special needs of Indigenous elders, women, youth, children, and persons with disabilities.

- Lack of evidence of Indigenous rights expertise, and local experience among those conducting the assessment (e.g., impact assessment conducted only by engineers).

- Lack of information relevant for understanding whether and how each potentially impacted community has been involved in, and verified, the impact assessment's outcomes.

Red flags in company practice

Examples of red flags in company practice, e.g., as self-reported by companies, reported by media, data providers, NGOs, and Indigenous peoples’ own social media channels:

General

- A track record of adverse human rights impacts or allegations of adverse human rights impacts, including allegations of adverse impacts in other geographic locations.

- Company executives, board members, or major individual shareholders that have a track record of being involved in adverse human rights impacts.

- Aggressive public relations campaigns and overt disclosure on charitable activities, community benefits, and development related to potentially impacted Indigenous peoples, which can be a tactic to legitimize activities that fail to respect Indigenous peoples’ rights.

- Dismissal of or non-response to the concerns of legitimate Indigenous representatives and decision-making institutions.

- Language that uses Indigenous rights and FPIC only in relation to terms that concern risks to businesses rather than to rightsholders, such as “social license to operate,” “land access strategy,” or “conflict management.”

Due diligence

- Lack of dedicated staff responsible for identifying, assessing, and addressing the company’s potential and actual human adverse human rights impacts.

- Lack of a due diligence process to identify, mitigate, or prevent adverse human rights impacts caused by third parties, such as government agencies, contractors, joint venture partners, or security forces.

- Lack of company grievance mechanism to which Indigenous peoples have agreed, which sets out processes to receive, investigate, and remediate actual or potential impacts.

- Reliance solely on domestic standards rather than international human rights law and standards.

Government agreements

- Agreements signed with host States that lack provisions to guarantee respect for human rights.

- Investment contracts signed with host States about which potentially impacted Indigenous peoples have not been consulted in a FPIC process, or to which they have not given their consent.

- Lack of evidence that Indigenous peoples have been consulted about and given their consent prior to the allocation of concessions that overlap with Indigenous peoples’ lands and territories.

Community agreements

- Widespread use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) in “consent” or “memorandum of understanding,” or “benefit sharing” agreements that prevent external verification of FPIC. Such agreements can also prevent Indigenous peoples from exercising their right to FPIC, e.g., by seeking independent expert advice.

- Signs that consent was not freely given, e.g., signs of intimidation, threats of militarization, or presence of public or private security forces during negotiations.

- Signs of “trap-like” agreements that contain provisions that limit Indigenous peoples’ access to their rights and lands, or provisions that limit Indigenous peoples’ ability to exercise self-governance within their territories.

- Contracts or benefit-sharing agreements that impose obligations on Indigenous peoples, but do not impose any obligations for companies (except for benefit-sharing), e.g., agreements where benefits to communities are conditional on giving up their rights.

- Benefit-sharing agreements which are contested by Indigenous peoples’ legitimate representative institutions.

Investments in complex ownership structures

Investors can be exposed to adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples through mergers and acquisitions (M&A) of investee companies, joint venture participations, and investee companies’ subsidiaries. Where a company is involved in a merger or acquisition, the UN Guiding Principles set out that it should conduct human rights due diligence to identify and address actual or potential impacts. When a company is involved in a joint venture, it is expected to have strong legal and other agreements to ensure that human rights are respected.236

Thus, when investing in companies that may be involved in complex investment chains and ownership structures, investors should also assess investee companies’ due diligence practices and legal agreements to ensure human rights are respected.

Questions to consider

- Does the company have a due diligence process that considers Indigenous rights in relation to minority shareholdings, mergers and acquisitions, and joint ventures?

- What contractual agreements are in place in relation to mergers and acquisitions to ensure Indigenous rights are respected?

Red flags

- No policy commitment to respect the rights of Indigenous peoples, or one that does not explicitly require business partners, such as joint venture partners and subsidiaries, to respect Indigenous rights.

- Lack of a grievance mechanism through which affected people can raise concerns, which also includes complaints related to joint venture partners, subsidiaries, and other business partners.

- Companies that evade their human rights responsibility by selling their stake in subsidiaries without mitigating/preventing impacts and seeking to enable or provide remedy.

Case Study: ArcelorMittal and Ternium Joint Venture

The Peña Colorada Consortium is a joint venture between ArcelorMittal and Ternium, operating the Peña Colorada Mine in Jalisco, Mexico. Several civil society organizations reported attacks against Indigenous peoples related to their opposition to the Peña Colorada mine. Mapas Conflictos Mineros en Latinoamerica (OCMAL) reports that community members have been threatened, assassinated, and disappeared. According to OCMAL, the number of assassinated community members in relation to this conflict amounts to 35.237

Impacts in the upstream supply chains of downstream companies

Companies that may be linked to impacts in their upstream supply chain include but are not limited to traders of agricultural products and food and beverage companies, and companies in renewable energy value chains such as battery manufacturers and electric vehicle manufacturers.

In some commodity value chains, particularly in the palm oil value chain, NDPE policies have been widely adopted. A growing number of companies have also started to publicly disclose grievances in the value chain and lists of suppliers and (palm) mills from which they source products.

In practice, even companies that score highly on various benchmarks have failed to enable adequate remedy,238 and those whose human rights are affected rarely if ever have access to just and equitable remedy. Thus, investors can presume that, in most cases investee companies in global commodity value chains currently lack adequate processes to provide or cooperate in effective remediation.

Questions to consider in investment due diligence and engagement include:

- Does the company require its own operators and suppliers to respect Indigenous peoples’ rights? Does this requirement apply to all operations and suppliers, across all products and commodities?

- Does the company require its own operators and suppliers to obtain FPIC before commencing any activities on their lands? How does it implement this policy in practice?

- Where a company “expects” suppliers to respect Indigenous rights, what is its process to identify impacts on Indigenous rights, and to exert leverage over suppliers?

- What is the company’s policy and operational procedure for when its own operations or suppliers fail to respect Indigenous rights and FPIC?

- What steps has the company taken to ensure traceability in its value chain? Does it impose requirements on direct suppliers to disclose its supply chain and grievances?

- What steps has the company taken to verify, through an independent third party, compliance with FPIC by its own operators, suppliers, subsidiaries, or other business partners?

- What steps has the company taken to ensure its grievance mechanism is accessible to affected people? Is it accessible in all relevant languages?

- What procedure does the company have to handle cases in which complainants are at risk of reprisals?

- Has the company developed a time-bound plan to investigate and enable remedy for unresolved grievances in its value chain?

Impacts in the downstream value chain of companies

Businesses can be involved in adverse impacts in their downstream value chain, e.g., by providing products and services, engineering, equipment, machinery, construction, and other services to projects such as mining, infrastructure, and renewable energy projects.

Questions to consider in investment due diligence and engagement include:

- Does the company provide products or services to customers or projects that operate near or on Indigenous lands? Are projects and project locations publicly disclosed?

- Does the company have a due diligence process to identify and address human rights issues in the downstream value chain?

- How does the company screen potential projects and customers? What is the methodology and scope?

- How does the company identify and assess risks of violations of Indigenous rights? How does the company assess whether a project has obtained FPIC of potentially affected Indigenous communities?

- Does the company have a process to provide for or cooperate in the provision of remedy? Does the process apply to impacts that occur in the downstream value chain?

- Can the company provide examples of cases where an assessment of actual or potential human rights impacts affected its decision to proceed or not with a customer or project?

- Can the company provide examples of cases where it has used its leverage to mitigate or prevent adverse impacts on the human rights of Indigenous peoples in its downstream value chain?

Response to identified adverse impacts:

- What steps has the company taken to cease, prevent, and mitigate actual or potential impacts?

- Has the company made a time-bound plan to use its leverage to cease, prevent, mitigate, and enable remedy regarding the adverse impacts?

- Has the company consulted with potentially impacted Indigenous peoples or civil society organizations with regards to appropriate actions to mitigate, prevent, and enable remedy?

Investments in banks

Banks can contribute to or be linked to adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples’ rights by providing finance to projects or companies that fail to respect Indigenous rights. Questions for investors to ask banks include:

- Does the bank have a commitment to respect Indigenous peoples’ rights as articulated in the UNDRIP that applies to all its activities, including all types of finance and corporate finance advisory services?

- Where a bank has a policy that “expects” clients to adhere to e.g., FPIC, or IFC (International Finance Corporation) Performance Standard 7, but does not explicitly require it, how does the bank translate this “expectation” into its due diligence process to use its leverage in cases in which clients do not have FPIC?

- Can the bank set out how it applies this policy in the case of general corporate finance to companies that may require FPIC across a range of projects?

- Can the bank describe, and give an example of, how it applies this policy to corporate finance advisory or other financial services?

- Is the bank able to point to examples of how it has used its leverage in practice to ensure that the rights of Indigenous peoples, including FPIC, is respected? Is the bank able to point to examples of steps it has taken to address the impacts concerned where the bank found out that FPIC was not obtained?

- Does the bank have a grievance mechanism in place or participate in a grievance mechanism for people, to receive and investigate, and enable remedy for human rights impacts, including with respect to Indigenous rights? How does the bank know whether the grievance mechanism is effective?

Case Study: BNP Paribas and the Royal Lestari Utama Project

The Royal Lestari Utama project was set up as a joint venture between tire manufacturer Michelin and Indonesian Barito Pacific Group, which aimed to produce “eco-friendly” rubber. The project was financed by “Sustainability Bonds,” for which the French bank BNP Paribas acted as the arranger, or lead manager. Investigations by Mighty Earth and Voxeurop found that while the project has been marketed as sustainable, the project failed to consult and obtain consent of Indigenous peoples and destroyed forests home to Indigenous peoples.239

Investments in real assets or projects

Investors in real assets or projects may have better access to the geographical information of the project and potential impacts compared to companies with geographically diverse operations. Investors investing in real assets or projects may also have greater control over the project or asset, and therefore have heightened due diligence expectations.

Some project developers seeking financing for their projects have policy commitments to conduct due diligence in accordance with the IFC Performance Standards; the Equator Principles; or the World Bank Environment, Health, and Safety (EHS) standards; to address their social and environmental risks, including with respect to Indigenous peoples. While these standards have language on Indigenous peoples’ rights, they also have weaknesses, and investors should not assume that the existence of such policies means Indigenous peoples’ rights are or will be respected.

Investors should take additional steps, e.g., by using the FPIC Due Diligence Questionnaire developed by First Peoples Worldwide. Where relevant, investors may, in consultation with potentially impacted Indigenous peoples, commission a Human Rights Impact Assessment (HRIA) using as guidance, for example, the Forest Peoples Programme’s Stepping Up due diligence guidance.

Case Study: Lake Turkana Wind Project in Kenya

The Lake Turkana Wind Project (LTWP) is a wind farm located on Indigenous peoples’ land in Kenya. Despite its claims of adhering to the IFC Performance Standard 7 on Indigenous peoples, it has faced opposition by Indigenous people, and the Kenyan Environment and Land court has ruled that the process for acquiring and leasing land was illegal.

- In 2011, a report found that the project was broadly compliant with the IFC Performance Standard 7 on Indigenous people.240

- In 2014, representatives of communities filed a lawsuit for illegal land acquisition. Several organizations reported that the project did not have FPIC of Indigenous peoples.241

- In 2016, the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre asked Lake Turkana Wind Power company under what circumstances the company commits to seek FPIC to a project. Management responded that they follow the IFC Performance Standards and found that it was not required to undertake FPIC.242

- In 2021, the Kenyan Environment and Land Court ruled that the process for acquiring and leasing land for the project was illegal.243

Carbon credit schemes, nature-based solutions, conservation programs

Recent years have seen an increase in the demand of carbon and biodiversity credits, often on Indigenous territories in tropical forests. Those programs, often marketed as sustainable development solutions, can lead to violations of Indigenous rights, e.g., by dispossessing Indigenous peoples of their territories, or using misleading contracts that restrict Indigenous peoples’ access to their lands and livelihoods. Questions for investors to consider are provided below.

Companies that produce, certify, or sell carbon or biodiversity credits:

- Has the company committed to respect internationally recognized rights of Indigenous peoples as articulated in the UNDRIP?

- Can the company provide maps demonstrating how proposed and existing projects overlap with territories owned, used, and controlled by Indigenous peoples?

- What is the company’s approach to ensuring that FPIC processes are fully informed? Does the company offer financial aid for Indigenous peoples to seek independent expert advice?

- What steps has the company taken to avoid unfair contract terms that may lead to restrictions of Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and access to lands, territories, and resources?

- What mechanisms are available to guarantee Indigenous peoples’ right to own, control, and use their lands, territories, and resources? What contractual mechanisms are available for Indigenous peoples to exit contracts if they revoke their consent to the project, e.g., because of not having been fully informed about project implications?

- Is the company transparent with Indigenous peoples about project details, including revenues and benefits arising from the project? Have Indigenous peoples agreed to a benefit-sharing agreement that they find satisfactory?

- What is the company’s approach to identifying any actual or potential land conflicts that may exist, which may be exacerbated by carbon or biodiversity offset projects? How does it know that it is not contributing to creating or escalating any conflicts?

Companies that use or purchase carbon or biodiversity credits:

- Does the company have a human right due diligence process that covers purchases of carbon or biodiversity credit schemes?

- What steps has the company taken to identify, and prevent/mitigate/remediate adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples’ rights caused by carbon or biodiversity credit schemes?

- From which companies and projects are carbon or biodiversity credits purchased? Do projects overlap with lands that Indigenous peoples own, use, or control by traditional ownership or which they have otherwise acquired?

- Do projects from which carbon or biodiversity credits are purchased use standards that require respect for internationally recognized rights of Indigenous peoples, and to obtain Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Indigenous peoples, above and beyond compliance with national regulation?

- Do projects from which carbon or biodiversity credits are purchased require fair and equitable benefit-sharing agreements with Indigenous peoples?

For reference, elements of rights-respecting practice could include:

- Engage in projects that genuinely seek to strengthen Indigenous peoples’ self-determination, their own decision-making mechanisms and institutions, legal recognition of land rights, and their capacity to protect and restore nature.

- Deliberately develop a process that ensures individual and collective rights of Indigenous peoples are respected throughout the project lifecycle.

- Ensure that project timelines are deliberately designed to give Indigenous peoples time to make decisions according to their own decision-making processes, which may include consulting internally with sub-communities, or externally with neighboring communities, and, where relevant, regional and/or national Indigenous organizations.

- Ensure Indigenous peoples have full, objective, and accessible information about project implications.

- Ensure that, as early as possible in the FPIC process, Indigenous peoples have access to independent expertise advice, including, if requested, capacity-building initiatives.

- Ensure that projects accepted by Indigenous communities are community-led and that benefits are shared equitably and in accordance with community agreements.

- Ensure that projects do not cause or exacerbate conflicts over claims of lands, territories, and resources.

- Transparently disclose the locations of all projects, including maps of overlaps with nearby, or overlapping Indigenous territories.

- Transparently disclose customers or purchasers of carbon or biodiversity credits and enable Indigenous people to choose not to sell carbon or biodiversity credits to traders of carbon credits or companies that fail to respect Indigenous rights.

- Transparently disclose information on revenues and benefits arising from projects, in a manner that is accessible to Indigenous communities, except for information that communities wish to be confidential.

Case Study: LEAF coalition

The LEAF coalition is a public-private partnership that seeks to finance “large scale tropical forest protection” and in return, participants will receive carbon offset credits. In June 2022, Amazon Watch published a briefer highlighting several issues with the initiative, particularly its approach to Indigenous rights and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent.244

The LEAF coalition will purchase credits that are certified and verified against the REDD+ Environmental Excellence Standard (TREES), which does not require adherence to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), does not mandate the development of equitable benefit-sharing programs, and maintains only partial commitments to FPIC with Indigenous peoples.

The standard used by the LEAF coalition allows for the implementation of Indigenous peoples’ rights safeguards to take place in accordance with national legal frameworks, which in many cases fail to include protection of Indigenous peoples’ rights in line with international human rights laws and standards.

7.3 Assess actual or potential human rights impacts

To meet their responsibility to respect human rights, investors are expected to assess their actual or potential human rights impacts. The starting point for assessing those impacts is to seek to understand the perspectives of Indigenous peoples concerned about actual or potential impacts, considering, inter alia, cumulative effects of previous encroachments or activities, and historical inequities faced by the Indigenous peoples concerned.245 Particular attention should be given to the rights and needs of individuals or groups within Indigenous communities that may face heightened risk of vulnerability or marginalization, by State and non-State actors, as well as within Indigenous communities.246

While Table 7 provides examples of questions to consider when assessing impacts, First Peoples Worldwide and Forest Peoples Programme have published further guidance for investors:

- Stepping Up: Protecting collective land rights through corporate due diligence: Due diligence guidance, which includes inter alia, guidance for community-level human rights impact-assessments, and for verifying whether FPIC has been given.

- Free, Prior, and Informed Consent Due Diligence Questionnaire: List of questions and considerations for investors and project developers to operationalize Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

Additional resources include the Akwé Kon Guidelines, the Danish Institute for Human Rights HRIA Toolbox, and the Indigenous Navigator Tools Database. Furthermore, the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business conduct (Q29-30) can be used as guidance to assess whether investee companies have caused, contributed to, or are directly linked to actual or potential impacts.

Table 7. Examples of questions to consider for assessing actual or potential impacts

| Rights | Questions (non-exhaustive) |

|---|---|

Non-discrimination |

|

Lands, territories, and resources |

|

Physical and mental health, life, security, and integrity |

|

Culture and cultural identity |

|

Environmental impacts |

|

Consultation, free, prior, and informed consent, and participation |

|

Self-determination, self-governance, and autonomy |

|

Note. For an overview of human rights instruments concerning Indigenous peoples’ rights, see Section 3 of this Toolkit.

Case Study: Right to cultural identity and property of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku

In 2002, the company Compañía Generales de Combustibles (CGC) and private and public security forces entered the territory of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku, to carry out oil exploration activities and seismic surveys, without the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent of Sarayaku. In response, the Sarayaku people, including elders, women, youth, and children, stopped their traditional way of life for four months, organizing themselves into “peace and life camps,” and expelled the company and security forces from their territories. In 2012, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that the right of the Sarayaku people to consultation, communal property, and cultural identity had been violated.

The Court considered that the Sarayaku people’s collective use and enjoyment of property based on their culture, practices, customs, and beliefs was necessary to ensure their survival, preservation of their way of life, customs, and language. Furthermore, the Court considered that their special relationship with their territories encompasses not just their subsistence, but rather “their own worldview and cultural and spiritual identity.”247