The investor responsibility to respect human rights

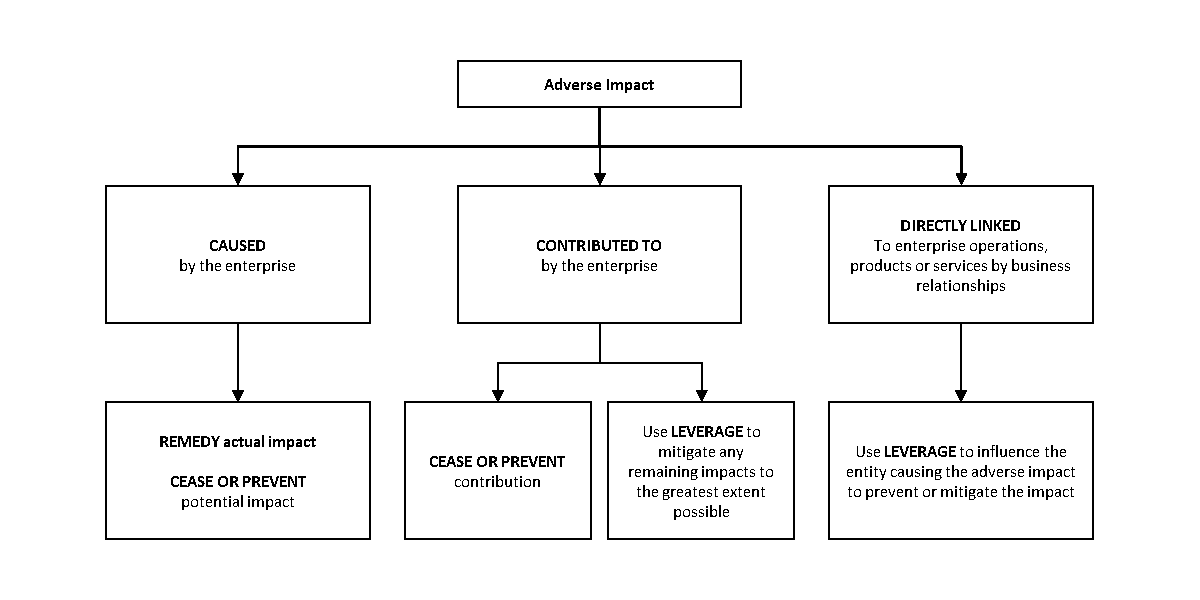

According to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, all businesses, including institutional investors, have a responsibility to respect human rights. These frameworks have established that institutional investors can contribute to or be linked to adverse human right impacts by their business relationships, e.g., by shareholding, providing loans, or investing in bonds. Where institutional investors contribute to or are linked to adverse human rights impacts by their business relationships, these frameworks stipulate that investors should use their leverage to cease, prevent, and mitigate human rights impacts. The understanding of the human rights responsibility of investors is still in a very nascent stage. However, it has been clearly established by the UN Guiding Principles and the OECD Guidelines that investors can contribute to or be directly linked to adverse human rights impacts.5

Figure 1. Responsibility of business enterprises under the OECD Guidelines.

It can be expected that in coming years these responsibilities will be further defined, and interpreted more comprehensively, through upcoming mandatory due diligence regulation, case law, and other work under human rights law. For example, law firm Hogan Lovells considers that a 2019 decision by the UK Supreme Court increases the likelihood that private equity funds could be liable for human rights impact of portfolio companies under common law in the UK, including for funds with assets in common law jurisdictions, such as Anglophone Africa, the Indian Subcontinent, Australasia and North America.6 Investors are also increasingly recognizing their human rights responsibility; in the European Union, various financial institutions have called for financial institutions to be included in upcoming due diligence regulation.7

Failure to respect Indigenous rights can lead to material risks for businesses and investors

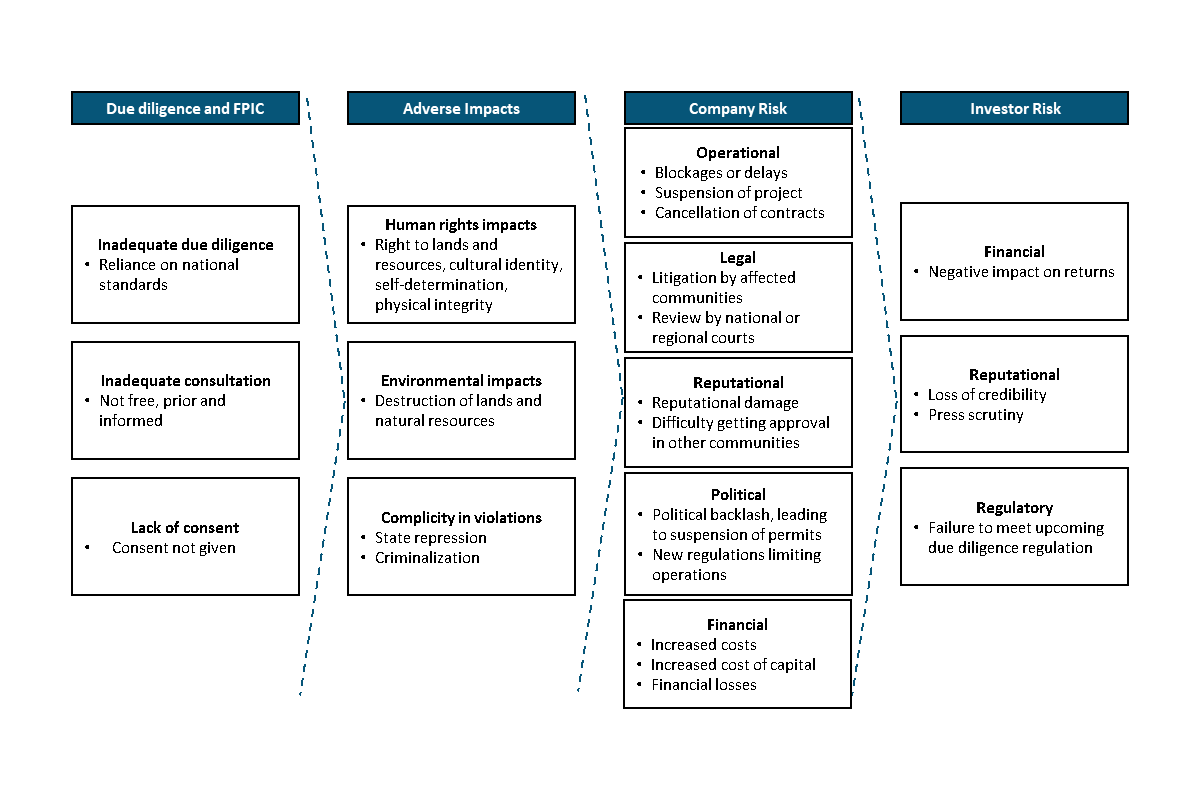

By failing to understand and conduct due diligence on Indigenous rights, investors may be ignoring material risks that may affect investee companies and, ultimately, investors. Numerous cases exist in which failure to respect Indigenous rights have had material negative impacts on businesses, such as financial losses, reputational damage, and cancellation of projects.8 In this regard, a study that examined the risks of community opposition and risks of Indigenous rights violations of 330 oil, gas, and mining projects, found that "leaders,” outperformed "laggards” by 4.2% in annualized returns between 2010 and 2014.9

Figure 2. Illustration of how failure to respect Indigenous rights may lead to investor risk

Source: Author’s elaboration

Companies and projects that do not have adequate due diligence processes and consent of Indigenous peoples risk underestimating the ensuing human rights and environmental impacts, which in turn can cause unforeseen risks for companies, such as:

- Operational delays, increased production costs, and permanent obstruction of projects: Operational risk can stem from community protests and blockades, which may delay or even permanently obstruct a project. This happened with oil company GeoPark, which alleged it lost at least US $70.8 million in investment in a failed oil project in the Peruvian Amazon, where Achuar and Wampis communities had vehemently opposed oil companies for decades.10

- Reputational damage, which can reduce access to capital and demand for products: Negative publicity caused by involvement in Indigenous rights abuses can cause reputational damage and erode social license to operate, as illustrated by the case of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s fight against the siting of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) on their treaty territory.11

- Legal and related obstacles and costs: Indigenous peoples adversely impacted by a project may initiate legal proceedings that could delay, change, or cause the cancellation of a project, such as local courts overturning concessions based on land rights violations, or lawsuits resulting from Indigenous rights abuses committed in connection with projects and activities.

The risks of investing in businesses that fail to respect Indigenous peoples’ rights are increasingly being recognized by investors. For example, BlackRock’s commentary on natural capital, in relation to its 2023 investment stewardship engagement priorities,12 states that:

[…] for companies whose operations impact Indigenous Peoples’ lands and legal rights, a failure to obtain, in advance and on an on-going basis, free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) from those Peoples may expose companies to increased legal, reputational or regulatory risk, in light of various local and international laws and norms governing these relationships.13

Companies or projects that fail to respect Indigenous peoples’ rights may also increasingly find it harder to get insurance for their activities. The statement of commitment from the UN-convened Net Zero Insurance Alliance includes a commitment to promote human rights, including the right to FPIC as articulated in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.14 Several Insurance companies have started to adopt policies on Indigenous rights and Free, Prior, and Informed Consent, including, Axis,15 Allianz,16 and Swiss Re.17 In October 2022, Axis explicitly committed not to provide insurance for projects undertaken on Indigenous territories without their FPIC.

In some industries it is common practice to include references to Indigenous rights in formal human rights policies.18 However, corporate policies on Indigenous rights are often ambiguous or inadequately implemented.19 Thus, when conducting due diligence, investors should go beyond looking solely at corporate policies and disclosures, and triangulate such information with other sources of information, in order to identify and avoid the associated risks.

Case Study: Dakota Access Pipeline Reputational Impact for Financial Institutions

In July 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe protested and filed a lawsuit against Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), to which they had not given their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent. As reports of violence, threats, and intimidation against protestors spread through news channels and social media, the protest gained worldwide support, leading to pressure on banks to divest from the project.

In October 2016, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council ended their relationships with financial institutions that invested in, or otherwise financially supported, any aspect of the Dakota Access Pipeline. Many Indigenous and non-Indigenous civil society organizations also urged banks to divest from the project. In November 2016, a letter signed by over 500 organizations was sent to the seventeen banks involved in a loan arrangement to DAPL, demanding the banks put payouts to the project on hold.20 It is alleged that this led to several banks divesting from the loan, and institutional investors, including Nordea, KLP, and Storebrand, selling their shares.21

As a result, Energy Transfer Partners, the operating company of the Dakota Access Pipeline, not only suffered reputational damage, but also reportedly incurred high financial costs followed by a drop in share price. The original estimated cost of the project was $3.8 billion; however, First Peoples Worldwide estimates that the actual cost was closer to $7.5 billion.22

Case Study: EDF Wind Project Canceled in México

In 2017, the French company EDF Renewables Mexico was granted construction permits for the Guuna Sicarú project in Mexico, without having conducted appropriate consultation with the Zapotec Indigenous community of Union Hidalgo. After community members of the Zapotec peoples raised concerns that the project had not undergone appropriate consultation processes, the Mexican government initiated a consultation process that was rife with threats, intimidation, and attacks against human rights defenders. After delays and civil lawsuits were brought against EDF, the Mexican Ministry of Energy canceled the contract with EDF Renewables México,23 and suspended the consultation, thus cancelling the project.24

Case Study: KGHM Ajax Mine rejected by Indigenous legal process

KGHM Ajax Mining Inc. proposed an open pit gold and copper mine near Kamloops, BC, Canada. The mine would have impacted Jacko Lake, also known as Pípsell, a sacred site to the Stk’emlupsemc te Secwepemc Nation (SSN) in whose territory the mine was proposed. The SSN conducted a review process pursuant to their own unextinguished Indigenous laws and rejected the mine in 2017.25 Following the SSN decision, the BC and federal governments both rejected the mine through their own processes.26

Protecting Indigenous rights is critical for addressing systemic risks arising from nature and biodiversity loss

Nature loss is increasingly being recognized as a systemic risk for businesses, investors, and society at large.27 A report by the World Bank, for example, estimates that biodiversity loss and reduction of ecosystem services could lead to significant declines of the world’s GDP in 2030, including over 10% in low-income and lower-middle income countries.28 It is also increasingly recognized that protecting Indigenous peoples’ rights is one of the most effective ways of halting nature loss.29

Research across various countries and regions find that forests in Indigenous territories are better conserved,30 and that legal recognition of Indigenous rights and territories is critical for preventing deforestation.31 Research has also found that projects that fail to respect Indigenous peoples‘ rights and needs are associated with greater environmental damage.32 In this context, the Forest Declaration Assessment, a multi-stakeholder initiative focused on meeting 2030 deforestation goals, has recommended that in order to meet the goals set out in the New York Declaration on Forests, governments should recognize Indigenous peoples’ rights and enforce mandatory FPIC, in addition to other interventions.33 The role and rights of Indigenous peoples are also recognized by the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework.

Some investors have also recognized the key role that Indigenous rights play in biodiversity protection. Storebrand’s 2022 Policy on Nature, for example, states:

Securing Indigenous Peoples’ customary rights is widely recognized as the most effective way of protecting biodiversity and ensuring sustainable use of nature. Storebrand Asset Management expects companies to respect Indigenous Peoples’ human rights, including rights to lands, territories, and resources, and to apply international best practice in seeking their Free, Prior, and Informed Consent for business activities that may affect them.34

While many Indigenous peoples have taken leadership in protecting nature, Indigenous land and environmental defenders face an uphill battle in protecting nature, as they often face serious threats to their security and life. Indigenous land and environmental defenders are frequently the target of attacks, including threats and assassinations, often in relation to business activities.35 As such, efforts to address nature-related systemic risks must also ensure that Indigenous peoples and their rights, are recognized, protected, and respected.

Government non-compliance with international and domestic law increases the risk of Indigenous rights violations

While some companies have committed to respect internationally recognized rights of Indigenous peoples, other companies simply seek to comply with national legislation or government requirements. However, governments often fail to adhere to their own international and domestic obligations, increasing the risk of violations of Indigenous peoples’ rights and the subsequent involvement of international, regional, or domestic courts.

Several examples exist in which international, regional, and domestic courts have ruled that concessions or permits granted by governments to private-sector actors were illegal and have ordered national governments to suspend concessions due to failure to respect Indigenous peoples’ rights.36 Such court decisions do not solely reference instruments explicitly related to Indigenous peoples, such as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples (UNDRIP) but also a multitude of international instruments, and domestic regulation.

Case Study: Court Ruling on Mining Concessions in Ecuador

In 2017, the Cofán de Sinangoe people filed a complaint with the Constitutional Court of Ecuador due to 20 mining concessions being granted to miners without consultation and FPIC of the affected Indigenous communities. While the government argued that there was no requirement to consult, the Constitutional Court of Ecuador rejected the State’s argument and ruled that the concessions were illegal.37 Some of the reasonings of the court include:

- Indigenous rights derive from traditional ownership, not from the State.

- Direct adverse effects on Indigenous peoples due to unauthorized intrusion.

- The right to a healthy environment had been violated.