This section provides an overview of the intersection between business-related activities and Indigenous peoples’ rights, including the current landscape of business standards and policies, and business-related human rights risks faced by Indigenous peoples.

5.1 Businesses-related human rights risks faced by Indigenous peoples

As Indigenous peoples face a heightened risk of social and economic marginalization, they are also among the groups most severely affected by business-related activities, particularly by the extractives (oil, gas, and mining), agribusiness, and energy sectors.172 Those impacts are also often exacerbated by remoteness and cumulative discrimination, which means Indigenous peoples may simultaneously be affected by multiple forms of discrimination and human rights risks and impacts that other groups individually face.173

The disproportionate level of negative impacts of corporate activities on Indigenous peoples, and Indigenous human rights defenders in particular, have been documented in several studies.174 The most common types of documented attacks against Indigenous human rights defenders are judicial harassment, including arbitrary detention, and strategic lawsuits against public participation, followed by killings, intimidation and threats, beatings, and other forms of violence.175 According to the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, most attacks against human rights defenders, documented since 2015 were linked to mining, agribusiness, and renewable energy sectors, with Indigenous people being subject to approximately 25% of these attacks, despite comprising approximately 5% of the world’s population.176

Oil and gas

The extractives sector, in particular oil and gas, has generally been seen as the worst human rights offender in relation to Indigenous peoples. A study found that the extractives sectors “account for the most allegations of the worst abuses including complicity in crimes against humanity. These are typically for acts committed by public and private security forces protecting company assets and property; large-scale corruption; violations of labor rights; and a broad array of abuses in relation to local communities, especially indigenous people.”177 In the Environmental Justice Atlas, which documents stories of communities struggling for environmental justice, Indigenous peoples were affected in 67% of documented socio-environmental conflicts in the oil and gas sector.178

Case Study: Oil concessions on Indigenous territories in the western Amazon

In the western Amazon (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia), Indigenous peoples’ territories have been divided into oil concessions without the consent of Indigenous communities. Research from Mongabay has found that in these countries, a total of 1647 Indigenous territories overlap with oil concessions. The percentage of Indigenous communities that overlap with oil concessions is approximately 74% in Ecuador, 61% in Peru, 41% in Colombia, and 36% in Bolivia.179 Indigenous communities in the western Amazon have repeatedly suffered severe impacts from oil spills, including consequences on food security, health, environmental damage, and access to water.

Mining

Although the mining sector has taken steps to recognize Indigenous peoples’ rights in the last few decades, the gap between industry standards and actual practice is still wide.180 While in some parts of the world, Indigenous communities have entered benefit-sharing agreements with mining companies,181 data from the Environmental Justice Atlas data shows the mining sector to be the sector with the highest occurrence of assassinations, physical violence and criminalization of land defenders, particularly where Indigenous peoples are affected.182 Moreover, evidence from around the world shows that the rights of those who do not consent to mining projects have rarely been respected. For example, a study found that lack of consultation and FPIC has been the norm of Canadian mining companies in Latin America, not the exception.183 As of 2023, Indigenous peoples were affected in 47% of the mining-related socio-environmental conflicts documented in the Environmental Justice Atlas.184

Whereas the International Council on Mining and Metals’ (ICMM) 2013 position statement on Indigenous peoples and its 2015 good practice guidance on Indigenous peoples may be seen in the industry as a reference for good practice, its language on what happens if consent is not given “risks allowing members to pursue projects in the absence of FPIC, putting them in a position where they are potentially complicit in State violations of indigenous peoples’ rights.” Moreover, several members have fallen short on its policies, particularly regarding human rights violations.185

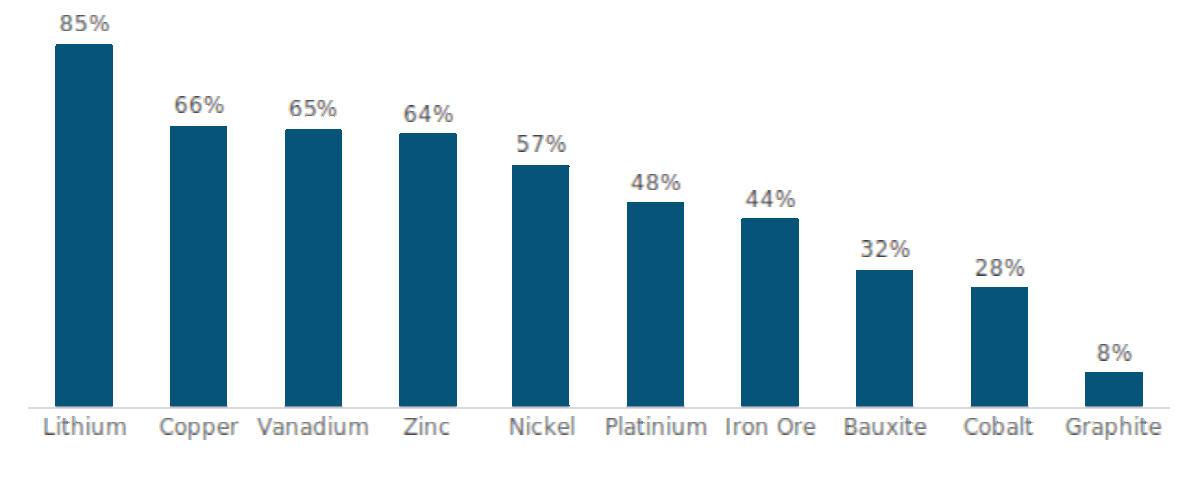

Figure 3. Percentage of energy transition mineral projects located on or near Indigenous land

Human rights risks to Indigenous peoples are also driven by increased demand for minerals in relation to the transition to renewable energy. A study published in June 2022 estimated that 54% of “energy transition mineral projects” are located on or near Indigenous lands.186 Transition minerals can also affect Indigenous peoples’ water rights in relation to seabed mining, which is a concern of Pacific Indigenous peoples.187 The Sirge Coalition has further elaborated on the issue of transition minerals and Indigenous rights.

Agribusiness

Agribusiness-related adverse impacts on Indigenous peoples’ rights stem from land-grabbing and destruction of Indigenous lands for timber and pulp, rubber, agricultural plantations such as palm oil and soy, and for cattle ranching.188 Many of the worst aspects of modern agribusiness practices have their origins in colonial systems and structures of violence, which relied on stolen land seized from Indigenous peoples and slavery, forced labor, and similar practices.

Those commodities are typically exported to food and beverage manufacturers, or other sectors, through commodity traders such as ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus.189 Downstream food and beverage manufacturing companies have argued that it is challenging to trace their commodity supply chains. Despite the challenge, companies have a responsibility to avoid human rights abuses and to enable remedies for adverse impacts to which they are directly linked. Institutional investors are linked to those adverse human rights impacts not only through shareholdings of commodity traders and downstream food and beverage companies but also by providing financing to intermediaries and upstream producers and suppliers.190

Case Study: Financing of Indigenous rights abuses in Indonesia

In 2021, a coalition of various NGOs published a report that shed light on how household name companies including Nestlé, PepsiCo, Wilmar and Unilever and various financial institutions (including but not limited to ABN Amro, Rabobank, Standard Chartered, and BlackRock) were allegedly connected to ten palm oil plantations involved in human rights and Indigenous rights abuses in Indonesia. According to the report, palm oil from the plantations ended up in the supply chains of global brands, while the operations of those plantations were financed by several major financial institutions.191

Renewable energy

Although the extractives and agribusiness sectors have historically been seen as responsible for the worst human rights abuses on Indigenous peoples, the renewable energy sectors are also increasingly severely affecting Indigenous peoples. According to the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, “The most serious and commonly occurring human rights issues in the RE sector include the failure to respect the right to FPIC of Indigenous Peoples, [and] land rights abuses in relation to involuntary resettlement and compensation.”192 The Centre’s report notes that “Between January 2015 and August 2022, out of 883 documented attacks against Indigenous human rights defenders, at least 134 were related to renewable energy projects, including hydropower, wind, and solar.”193

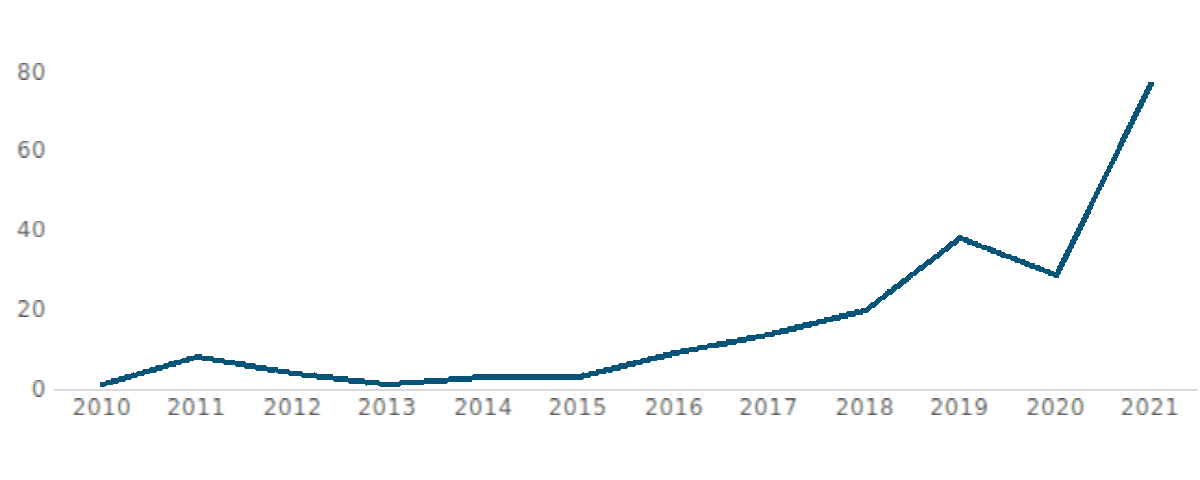

Figure 4. Number of allegations linked to renewable energy projects recorded by the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre.

In 2018, the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre published guidance for investors regarding renewable energy investments which showed that Indigenous rights were at particular risk across each of five sub-sectors of renewable energy development: wind, solar, bioenergy, geothermal and hydropower.194

In 2021, the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre published the Renewable Energy Human Rights Benchmark, which found that the overall number of allegations of human rights abuses in the renewable energy sector had increased at a rapid pace since 2010. Moreover, it found that companies in the renewable energy sectors overall were not adequately addressing their human rights risks; they scored particularly low on their most salient risks, including Indigenous peoples’ rights, land rights, and protection for human rights defenders.195

Carbon credits, offsetting schemes and nature-based solutions

Carbon credit schemes involve an actor (typically a company or government) paying for projects intended to mitigate carbon emissions, such as renewable energy development or forest protection. The actor paying for the project receives carbon credits intended to represent the carbon emissions mitigated by the project. Payment through carbon credit schemes is often billed as a sustainable development option for Indigenous peoples, whose territories in forests or grasslands that function as carbon sinks are seen as having potential for land-based carbon offsets, commonly referred to as “nature-based solutions.”

Carbon credit schemes have been criticized, as projects have suffered from systemic over-crediting and exaggeration of climate benefits,196 and in many cases, posed severe threats to Indigenous rights. Many offset projects have failed to respect the right to FPIC; failed to share benefits with Indigenous communities; and often restricted the rights and livelihoods of or even displaced Indigenous peoples from their territories.197 As of 2023, Indigenous peoples were affected in 61% of the socio-environmental conflicts related to “carbon offset” projects in the Environmental Justice Atlas.198

Case Study: Total Energies and Shell Carbon Offsets in Peru

Carbon credit programs in Peru, sold by the company Ecosphere+, from which Total Energies and Shell have bought carbon credits (according to the Associated Press), have allegedly restricted access to lands and livelihoods of the Kichwa People of San Martín, in what the Peruvian government has declared the Cordillera Azul National Park. Although there is evidence that the Kichwa People of San Martín have traditionally hunted inside what is now a national park, the Peruvian government argued that there was no need for consent of the Kichwa people, arguing that it was never their territory. In recent times, the Kichwa People have started organizing themselves, demanding compensation, or restitution of lands. According to many Kichwa people concerned, carbon credits have not protected the park; rather, the Kichwa People themselves carry out patrols to confront illegal ranchers and coca growers.199

Case Study: Carbon Credits in Guyana

The South Rupununi District Council of Guyana, legal representative of 21 Indigenous communities, sent a letter to the Guyanese government asking them to legally recognize and title their lands. The Council states that only once land titles are legally secured, would it be appropriate for them to decide whether and how to participate in carbon credit programs.200

5.2 Indigenous rights in corporate standards

Over recent years, a range of businesses and sectors have become increasingly aware of the critical importance of improving their knowledge and action on Indigenous rights. While international financial institutions such as multilateral development banks and development finance institutions, as well as commercial banks, have developed standards and policies on this issue, institutional investors, including asset owners and asset managers, are among the most recent to join the list of those growing their awareness of this issue. This section highlights examples of key standards that refer to Indigenous rights. However, it also seeks to caution investors that, in practice, these standards often fall short on protecting Indigenous rights.

IFC (International Finance Corporation) Performance Standard 7

In some sectors and regions, it is widespread practice have policy commitments to adhere the International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standard 7 on Indigenous peoples, which states that it seeks to “ensure that business activities minimize negative impacts, foster respect for human rights, dignity and culture of indigenous populations, and promote development benefits in culturally appropriate ways.” The standard is a requirement for companies seeking loans from the IFC and has also been adopted as a standard by the Equator Principles, a risk management framework for financial institutions (see below). As such, companies seeking project finance from the IFC or from Equator Principles Financial Institutions should, on paper, adhere to the standard.

The IFC Performance Standards and Equator Principles are not fully aligned with the UN Guiding Principles nor with the UNDRIP and internationally recognized rights of Indigenous peoples.201 The IFC Performance Standard 7 requires Free, Prior, and Informed Consent in certain circumstances; however, it has been criticized for leaving room for interpretation in its implementation.202 Moreover, research has shown that even the IFC itself has not adequately implemented its standard in projects where Indigenous peoples were present.203

The Equator Principles

The Equator Principles are a risk framework for financial institutions (typically banks and credit export agencies) to assess and manage environmental and social risks in their finance for projects. In non-OECD countries, the Equator Principles require signatory financial institutions (EPFIs) to evaluate, with the support of an independent consultant, a project’s adherence to the IFC Performance Standards and the World Bank Environmental, Health and Safety (EHS) standards, and in OECD countries, a project’s compliance with host country laws.

However, the Equator Principles’ focus on project finance means that corporate-level finance is not subject to the scrutiny promised by the Principles. Furthermore, the latest version (EP4) has received criticism for its weak and non-committal language, which, according to First Peoples Worldwide, “renders it instantly obsolete, especially for those financial institutions seeking to catalyze meaningful partnership with Indigenous Peoples to avoid social and environmental violence.”204

The weaknesses of the Equator Principles are also related to its inadequate implementation. In 2020, BankTrack reviewed 37 high-risk projects financed by Equator Principles signatories and found several inadequacies. While the Equator Principles require banks to ensure high-risk projects have stakeholder engagement processes and project-level grievance mechanisms, the report found that evidence of stakeholder engagement or project-level complaints mechanisms were missing in 24 out of the 37 projects analyzed, or 65%.205

Multi-stakeholder initiatives and certification programs

Increasingly, various sectors have come to acknowledge the importance of respecting, or at least being seen to address, Indigenous peoples’ rights. Several industry-driven multi-stakeholder initiatives have developed certification standards, which include criteria related to substantive and procedural rights of Indigenous peoples. Yet even best-in-class certification standards have loopholes and limited implementation in practice.206

Some of these initiatives, including the Aluminum Stewardship Initiative (ASI), Initiative for Responsible Mining Assurance (IRMA) the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), and the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) have included Indigenous representatives in the standard and certification development process. 207 Yet in practice, many certification schemes have often failed to implement their standards on Indigenous rights. A review of five certification schemes highlighted several challenges, such as lack of representation of Indigenous peoples in the governance structures of the multi-stakeholder initiatives, auditors’ lack of cultural awareness, and substandard assessments by auditing firms. Although the RSPO is considered the most robust standard, in some geographic regions there is a growing distrust towards auditors, due to a perception that because auditors are too close to the companies, they do not comply with the auditing requirements.208

The limitations of multi-stakeholder initiative certification standards have also been highlighted by the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, which found that they tend to lack transparent and independent monitoring mechanisms.209 The International Work Group on Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) has highlighted the issue that some businesses offset the implementation of their policies on Indigenous rights to those multi-stakeholder initiatives.210 A study of multi-stakeholder initiatives more broadly found that most are not rightsholder centric and have failed to protect rightsholders and remedy human rights impacts.211

Commitments to No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE)

Commitments to No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) have increasingly been adopted by companies in agricultural supply chains (particularly in palm oil supply chains). While the terms “no deforestation” and “no development on peatlands” refer to avoiding deforestation and having no new developments on peatland, no exploitation refers to respecting human rights, including the rights of Indigenous peoples.212

NDPE commitments typically include not just companies’ own operations but also suppliers. While some actors point out that NDPE policies are among the most effective existing policies for addressing adverse human rights impacts in companies’ supply chains, others note that in order for these to function adequately, it would require the entire industry to implement such commitments, which is currently not the case.213 Another issue is that most NDPE policies often only cover one type of commodity (typically palm oil), which means that the policy is often not enforced for companies that cause adverse human rights impacts or deforestation in relation to other commodities.214

Corporate policies

References to Indigenous rights in corporate policies are increasingly common, although most companies still do not have such policies. In 2022, the World Benchmarking Alliance assessed close to 400 companies across 8 industries and found that just 13% had a clear commitment to respect Indigenous peoples’ rights.215 In 2021, the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre found that a quarter of assessed renewable energy companies had policies recognizing the rights of Indigenous peoples.216

Banks and financial institutions more broadly are also increasingly including FPIC in their policies but have fallen short on recognizing and committing to respect Indigenous rights beyond FPIC. Research by Global Canopy found that while 27% of the 150 financial institutions most exposed to deforestation had a commitment to FPIC for at least one commodity, only 6% had a policy to respect the rights to land, territories, and resources of Indigenous peoples.217

Moreover, policies are often weak and ambiguous, or inadequately implemented.218 The Responsible Mining Index 2022 assessed the 40 largest mining companies in the world and found that “While most companies make mention of their position on FPIC, only a few companies have made formal commitments to respect the rights of Indigenous peoples to FPIC.”219

Regulation on Mandatory Human Rights Due Diligence

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises have set a precedent for existing and emerging human rights due diligence legislation. Such legislation has already been implemented in some countries, e.g., in Norway, France, Switzerland, and Germany. Similarly, the European Commission is developing a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive and a regulation for deforestation-free products. While regulation is a necessary step, concerns have been raised that due diligence regulation reflects compromises made as a result of conflicting stakeholder demands, and as such, do not necessarily fully align with the UN Guiding Principles.220 As such, investors should not necessarily assume that the existence of human rights due diligence regulation guarantees that businesses act in a manner that is fully aligned with the UN Guiding Principles and OECD Guidelines, and which fully respects the rights of Indigenous peoples.